An Interview With Pinckney Benedict

Interview

DAM: “Miracle Boy,” the title story in your recent collection, is a great example of a story that will linger long after reading – there’s a feeling of transcendence to it and the way it was put together, as to how well boiled-down it is to the necessities of what the story needs. Is this reduction process something you consider while writing?

PB: Part of that really is just my attempt to capture a fabulous quality – to give my stories the quality of a fable, which is also one of the reasons that the characters aren’t named in “Miracle Boy.” The names of the boys that are used, we understand are not the names that their parents know them by. Eskimo Pie, Geronimo, and Lizard are the names the boys have given each other, like the list of names in a club. Because they are a tribe of boys in this case, and this adds to the idea of the fable, which may, as you said, help get to that transcendent quality and I appreciate that. As well, crafting a fable in the right story, it has to take place in a very definite world, and my hope is that this is a – it is not a world of contemporary detail. “Miracle Boy” is not a world of the Internet and cell phones and McDonald’s and so forth. And a world where much of that contemporary material is stripped away actually makes it difficult for storytelling. Most of my stories, if they take place in any real time or in any real place at all, which they don’t for the most part, will be set in a kind of 1970’s era Appalachia, the West Virginia in which I grew up, the West Virginia in which I was a teenager. That seems to me that it’s a much easier world from which to tell stories. I would find it very difficult to tell stories, and maybe its just writers of my age or generation, which incorporated the Internet and cellphones (even though obviously I don’t live without those things). Every car in my stories will have a carburetor.

DAM: With the idea of the fable in mind, what would you say is the lesson learned in “Miracle Boy?”

PB: I have to be pretty careful about that and turning “Miracle Boy” into a kind ofafterschool special, which it has been accused – being sentimental. You know what I mean that the kid becomes better or something like that. At the same time it seems to me not a bad thing for fiction to recognize that sometimes people actually become human beings. That’s really what that story is about or at least that’s how I see the story and what I hope the story talks about. It’s a little kid who’s basically – he’s an animal, he’s a lizard right? I mean that he’s reptilian in his attitude toward other people in the world and by the end of the story you see that he’s changed. Where by the title of the story you think that the obvious miracle boy is the kid who got his feet cut off and then reattached. But my hope is you say okay there’s this other miracle boy in the story. I don’t think it’s sentimental to believe that people can become human. It’s rare, but people can learn to be aware of the humanity of others – and that, being how so unlikely this is, it constitutes a miracle when it does happen. So, yes, there is the lesson of the fable, but I hope that it’s not as sentimental as that might make it sound.

DAM: Do you remember your first short story?

PB: That’s a great question. I mean I’ve always written pretty much as long as I can remember. At least I’ve made stories in various ways. My first really serious short story, my first short story that I would call part of my contemporary work, even though it’s never been published, was a story I wrote my senior year in high school called “Gigging” and it was about catching frogs. The main character, who was a kid not very different from me, who went out to a pond on his family’s farm, which is very much like my family’s farm, with a friend of his, who was a kid very much like my best friend, to go spear frogs at night – something that they had grown up doing. But this was their last night before the one kid, the kid who was like me, went away to Prep school, which I did when I was 13. It was the first story that I really explored my own material. And it was the first story I ever wrote that was set in West Virginia, Appalachia where all of my subsequent literary work has been set. It’s the first time I ever explored my own material, my own autobiography, the way I grew up, the place I grew up, the friends I had – that sort of thing.

DAM: What are some of the elements of a story set in Appalachia?

PB: The beauty of the Appalachian story is that you have all the richness of Appalachian English, which is an incredibly rich vein of English. I mean when you find Appalachians represented in popular culture, they tend to be represented simply and without a kind of elegant language – and elegant language is their birthright. In the Appalachians you grow up as close to the roots of Elizabethan English that exist anywhere in the world. There’s an American idiom in Appalachia that has not been over exposed, and even on a national level it hasn’t been very deeply explored.

DAM: For example when writing in the spring versus the winter, would say the seasons affect what you’re working on?

PB: There’s actually a very specifically winter story in my collection, in Miracle Boy and Other Stories, it’s a story called Mercy and it will be anthologized in the upcoming Oxford Book of the American Short Story. This was a story originally written to be read on the radio for a winter show they wanted to broadcast on Christmas. So I wrote the story about winter coming and freezing a bunch of horses. Throughout the story there’s the threat of starvation and death by freezing for these horses. That’s the pressure in that story, it’s the pressure of cold and it’s a very different sort of pressure from heat – and I usually tend to write about the heat. When I’m writing it is easy for me to write about the season we are in. That is when I’m in summer I tend to write stories where the pressure or some of the pressure of the story comes from heat. My novel Dogs of God takes place in a really, really hot summer when everyone is sort of swimming through an incredible amount of humidity and they are sweating to the verge of being driven either to madness or to inaction. That’s the power of the heat: madness or inaction. And I guess that’s the difference for me, heat makes my characters drop back, but in the cold they’re going to be more vigorous, as I know they have to generate body heat to stay alive. But either way, they are great forces, right? I mean it’s one of the great things about extremes and it’s something I see too little of in the work of my students and too little in a lot of the work I read – the willingness to expose characters to extremes the right way.

DAM: You have a very distinct working relationship with Joyce Carol Oates; how would you say it’s affected your voice as a writer?

PB: She made me a writer. Well, who knows you know, you can’t say what your life would have been, but she is the person most directly responsible for my becoming a writer. She saw in my work something really worth championing, she championed me a bit, she and her husband Ray Smith who is a lovely, lovely guy – they published my first book in my early 20’s and just her presence in the classroom (and again it may sound sentimental to say), but it was deeply inspirational. She is a person of immense dignity, you know when you see her, you know that she’s a serious person and so you know that what you’re doing in her presence is serious – like if she takes it seriously you know you’re not getting it wrong. That she never – I’ve never seen her pretend for a single moment that the work we were doing was better than it was. She was intelligent, hugely well read, her work ethic is absolutely beyond comparison, she was a phenomenal sympathetic teacher, very generous teacher and so for me, I mean it was the experience. I grew up in southern West Virginia, right? I didn’t meet writers. She was the first writer I remember spending any significant amount of time with. It was so obvious that if you could, if I could imitate her (and mine is a poor imitation of her), but if I could then it would be possible to live a life that was worth living. And I was incredibly fortunate that she was my original role model.

DAM: What’s one rule of writing that you never break?

PB: The one rule? I mean as far as the only rule I can think of, it is: don’t lie! Right? And when I say don’t lie, I mean of course us writers we lie all the time, we make up stuff all the time, but in this case, what I mean is that I try to never lie about what I know the nature of the world to be. I say never – I see writers do it frequently for their own convenience that they’ll shorthand how the world really is in order to make their story work the way they want it to work. And that’s a lie and a betrayal – the story should never betray the world. A story I’m writing shouldn’t falsify my experiences in the world.

DAM: What’s the one rule you always break?

PB: That’s funny. The one rule I’ve been breaking most recently and that I’ve broken I think in pretty much every story in “Miracle Boy” is the rule (at least in academia) where you’re supposed to write realist short stories – that 19th century Atlantic Monthly William Dean Howell’s story about the common man doing common things with no extraordinary effects. There are also so-called genre elements in almost all my stories now, I have monsters, I have werewolves, I have ghosts, I have weird miracles, and I have all of those things happening. So in some sense I suppose I’m no longer as literary as I was probably earlier in my career, which might be considered a rule to break.

DAM: What has been the hardest thing to write?

PB: I found my novel Dogs of God to be really hard to write. It was a big book, it’s a capacious book, like it has a lot of different story lines, and it has a lot of different characters. When it was reviewed in New York Times there were some lines regarding it, something that said about me: you know one fears of the sanity of the writer on such an intense piece of writing. And I’m proud of that line because in fact I do feel like in some ways I did risk my sanity when writing it. I remember finishing it and thinking that I might never write again, which was actually a kind of good feeling in retrospect.

DAM: What was the most fun project to write?

PB: One story was from a collection called, The Wrecking Yard. This was the last story in it. “Odom” was really fun to write because it’s about a guy who falls in love with dynamite and gets to go around blowing stuff up. He blows up trees, he blows up rocks and it was really fun to write about explosives and learn about explosives. I was giving myself gifts in the story to write about. I try to give myself gifts like this in my stories – you know, something that I would love to own but that is too expensive or exotic, like some cars, some guns (because I also love guns), I love writing about guns, or some object or some activity that I think would be really fun to use in real life or that I’d get to experiment with in a literary sense.

DAM: What was “Odom” about?

PB: It was about this father and his son who lived almost completely isolated in this place on the mountains. After the son leaves and the father is left alone up on the mountain he becomes really, really lonesome and he has a lot of dynamite – so he has to find some way to kind of fill his days and he fills it by blowing stuff up.

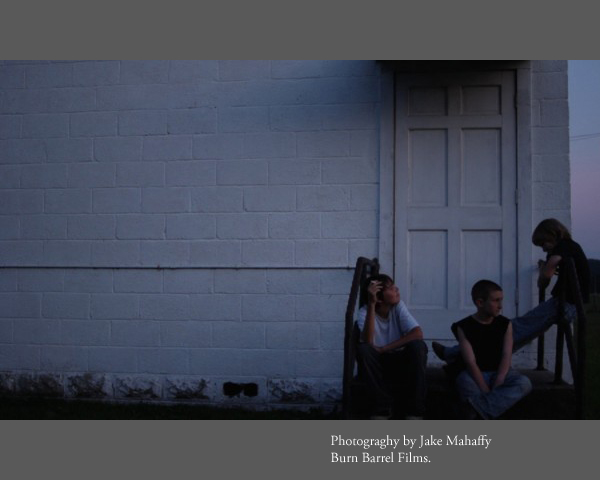

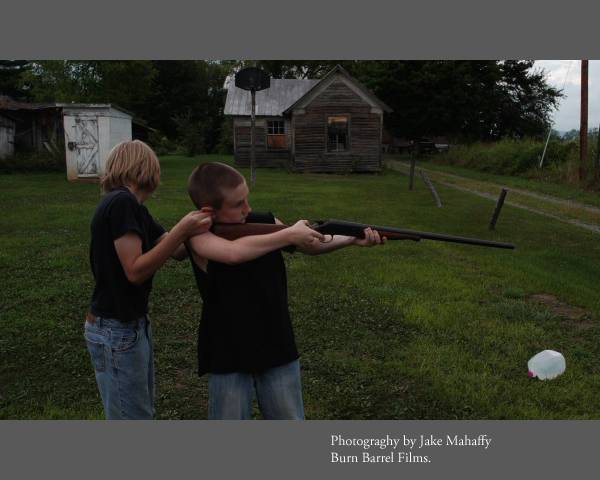

DAM: Tell me about the film version of “Miracle Boy” that is coming out?

PB: There is a young filmmaker named Jake Mahaffy from Burn Barrel Films who teaches at Wheaton College in Massachusetts and runs their film program. Last summer he went down to West Virginia, just 8 miles from where I grew up, to a town called Williamsburg and he shot a film version of “Miracle Boy” (which is currently in post-production). From what I’ve seen, it’s going to be a gorgeous, gorgeous film. To make the film he literally took the town over. He had complete access, from the historical society there, to shooting scenes in the big church they have in town, to having full-reign over a school there that’s been empty for about 3 years – they even planted an electrical pole in the ground where he needed it. And on top of which, basically all the actors are locals, non-union, non-actors. Local people played the parts – people that actually have the accents of the people that they are meant to have in the story, and which is really something.

DAM: How do you see the role of the writer?

PB: I think too often we get lost in other purposes. I mean our central purpose is to tell entertaining stories and I think too often writers have other agendas. We live in an incredible politicized age and I have strong political beliefs, I have strong religious beliefs also, but I’m not particularly interested in politicizing either of those things in my fiction. Really what I want to do first and foremost – and I’d be perfectly happy if it’s the only thing I do – is to tell a story that you would want to read and that having read the first line you’d think to yourself, wow, I want to see what happens to these people, I want to see what happens in this place, and I want to see what goes on here. Now, beyond that and beyond pure entertainment values you do hope that there is a kind of moral center to what you write.

DAM: Do you have a favorite word?

PB: There’s a dirty one, which I really, really like. I mean I love – yes that I fucking love. There’s so much flexibility built into it, and it’s etymology is comprised of all these parts – it’s a Heinz 57 of words, as it comes from all over the world and yet still so flexible – it uses the best parts of every culture that it’s ever come in contact with. I love the word “fuck” because it’s just – it’s a perfect word. Specifically, I mean it’s a perfect word because how its meaning changes to something very particular when its used as either a verb, adjective, or noun. And as well how you use it. I’d like to fuck you, for example, is really, really different from I’d like to have sex with you. Or I’d like to make love to you, or I would like to know you in the biblical sense of the word or anything like that. Right, fuck it, it’s just awesome.

Pinckney Benedict Bio: “Pinckney Benedict grew up on his family’s dairy farm in Greenbrier County, West Virginia. He has published four volumes of short fiction, the most recent of which is Miracle Boy and Other Stories. His stories have appeared in, among other magazines and anthologies, Esquire, Zoetrope: All-Story, Story Quarterly, Ontario Review, Appalachian Heritage, the O. Henry Award series, the New Stories from the South series, the Pushcart Prize series, The Ecco Anthology of the Contemporary American Short Story, and The Oxford Book of American Short Stories. He is the recipient, among other honors and awards, of a Literature Fellowship from the National Endowment for the Arts, a fiction grant from the Illinois Arts Council, two Plattner Awards for fiction from Appalachian Heritage magazine, a Literary Fellowship from the West Virginia Commission on the Arts, a Michener Fellowship from the Writers’ Workshop at the University of Iowa, and the Chicago Tribune’s Nelson Algren Award. He is a professor in the English Department at Southern Illinois University Carbondale.”

Close