Breaking Bad and the Myth of Individualism

- Weekend Read

- Sep 27, 2013

- 0 Comments

Welcome to the first Weekend Read from Digital Americana. Certain Fridays we will be presenting pieces that may take you a little longer to digest than our normal offerings. The debut piece, “Breaking Bad and the Myth of Individualism,” comes from the UK’s Simon Mussell, who questioned our “Land of Plenty” a few months back and here brings a unique look to one of the most American shows in recent history. With Breaking Bad coming to an end on Sunday, we felt it was the perfect piece to offer. Enjoy.

NOTE: THIS LONGFORM PIECE CONTAINS SPOILERS OF MAJOR PLOT POINTS OF BREAKING BAD UP THROUGH LAST SUNDAY’S EPISODE, “GRANITE STATE.” THE PIECE AND SPOILERS BEGIN AFTER THE PICTURE.

In the penultimate episode of Breaking Bad, we find Walter White ‘on the lam’. At once invoking and subtly parodying Henry David Thoreau’s beloved Walden, Walt finds himself holed up in a cabin in New Hampshire with only the most basic of amenities to hand. As the austerity of the environment intensifies the sense of his isolation, one of the underlying themes of the show comes to light. For beyond its virtuosic plot twists and dramatic set pieces, Breaking Bad offers some telling insights into the peculiarly American myth of individualism. In depicting the Promethean making and remaking of one Walter White, the show vacillates between celebration and denunciation, as it prompts us to contemplate the enduring appeal of what Herbert Hoover called ‘rugged individualism’. Through its complex alchemy of character, tone, environment and narrative, the show also highlights the potential pitfalls that might meet one who takes this myth of the omnipotent individual too seriously. In this article, the first of two on the subject, I will examine the most pervasive version of individualism, what I will call strong individualism. In doing so, I aim to better appreciate how it is that a nation’s self-image and culture came to be so strongly tied to an idea of the heroic (and anti-heroic) individual, and how this mainstay of American identity might be reinforced or undermined in series like Breaking Bad.

The varied meanings that might be subsumed under the term ‘individualism’ have a longer history than the term itself. For instance, one can find expressions of proto-individualist ideas in thinkers as diverse as Jean-Jacques Rousseau and Benjamin Franklin. But it was Alexis de Tocqueville who first coined the term ‘individualism’ and gave it a substantive meaning whose relevance and influence endure to this day. In his observations of American life in the 1830s, Tocqueville described individualism as a ‘mature and calm and considered feeling which disposes each citizen to isolate himself from the mass of his fellows and withdraw into the circle of family and friends’. The contemporary resonance of this provisional definition is testament to its robust legacy within the American psyche, its many iterations filtering into the national culture. As an important new addition to that national culture, Breaking Bad partakes in the re-articulation of this idea. This much is established from the outset, where it is clear that Walter White’s worldview closely conforms to Tocqueville’s definition of individualism. Walt’s moral outlook is extremely narrow, defined almost entirely by his tight-knit family. His ethical cartography permits little if any space to non-family members, as the long, grim litany of ‘collateral’ victims attests to. This moral myopia is nicely mirrored in the show’s location, which, as Robert Alford argues, serves as an apt backdrop to Walt’s contorted re-enactments of ‘frontier masculinity’. Indeed, as the series progresses, Walt most fully inhabits the Heisenberg persona when he ventures into the boondocks of New Mexico, the historical and cultural embellishments of the past perhaps at the back of his mind (and certainly at the forefront of the writer’s).

Frankly, there would be little to recommend the series if it were merely a restatement of such problematic refrains as frontier masculinity. Sure enough, in Breaking Bad the ordinarily straightforward trope of strong individualism that underpins so much of American culture (both past and present) is rendered ambiguous. As Walt’s swelling self-belief, arrogance and pride give rise to increasingly reprehensible actions and delusions, serving to inflate his ‘heroic’ alter ego and consolidate his drug empire, it is all the more effective when external forces (such as other people’s needs and demands, familial responsibility, complicated divisions of labour, financial redistribution, temporal limitations and other contingencies) re-enter the frame. The writers regularly indulge in the perpetuation of Walt’s self-aggrandizing (for example, in the outlandish closing scene of the episode ‘Say My Name’), even garnering our unlikely support for the character, before unceremoniously reversing his fortunes, unravelling all grand plans and debunking the myth of heroic individualism in the process.

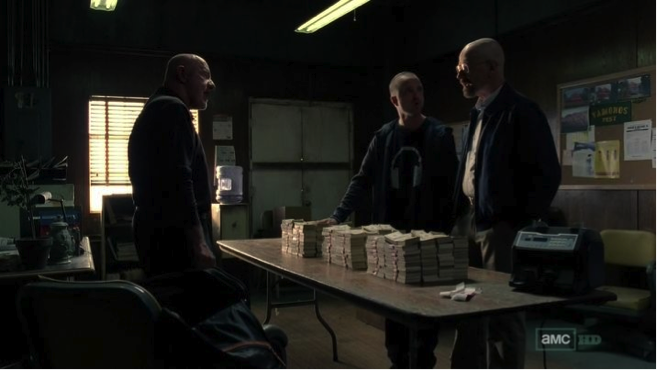

As the narrative of the series evolves, we learn that the same social, structural, interpersonal and economic factors that shaped Walt’s dejected, unfulfilling, ‘pre-diagnosis’ life come to undermine his attempts at self-determination. For instance, recall the moment in the episode ‘Hazard Pay’ when an angry Walt looks on as Mike divides up large piles of their cash in order to pay the various dealers, enforcers and mules, not to mention Saul Goodman and Vamonos Pest (in other words, the unseen workers whose extracted labour is essential to Walt’s success).

The resentment Walt harbours here is quintessentially individualist in the American sense. It is no different from that of those fabled ‘wealth creators’, the innovative, free-thinking individuals whose ‘hard work’ and inventiveness are apparently so rare and precious that they must be compensated for by greater tax relief and diminished social responsibility. Indeed, by this point in the series, Walt’s individualism has become so bloated that he cannot accept that his work, talent and earnings are unavoidably dependent upon that of others. One might say that he has become hyper-individualist. He has internalized and pursued the logic of individualism so resolutely that he now believes himself to be fully a ‘self-made man’.

This self-making might appear to be just another part of Walt’s dramatic ‘transformation’ from high-school chemistry teacher to crystal meth kingpin. (The show’s creator, Vince Gilligan, has even noted that as Walter became more sinister, his posture can be seen to improve and his gait becomes more upright). But if we cast our minds back to earlier seasons, Walt’s stubborn individualism was already well established at the time of his diagnosis. When his former colleagues at Gray Matter Technologies, Gretchen and Elliot – with all due tact and propriety – offer Walt a considerable compensation, more than enough to cover his medical costs, he flat out refuses. Similarly, he is uncomfortable to discover that Walter Jr. has been soliciting anonymous donations online (so much so that he enlists the aid of Saul, who suggests they might employ a hacker from Eastern Europe to use the website as a money-laundering device!). Walt’s misplaced pride and frontier-derived image of masculinity will simply not allow him to accept external assistance. Any resolution to his family’s economic woes must come solely from him, since he has internalized the ‘provider’ ideal that is part and parcel of strong individualism. As Walt’s former employer Gustavo Fring put it to him, ‘A man provides for his family … because he a man’. By now, the illogic of tautology is enough to animate the American family man.

In its restaging of masculine self-sufficiency, Breaking Bad speaks to another of the core precepts of individualism first observed by Tocqueville: ‘They [individuals] owe nothing to any man, they expect nothing from any man; they acquire the habit of always considering themselves as standing alone, and they are apt to imagine that their whole destiny is in their own hands’. This sentiment is replicated in the contemporaneous work of Ralph Waldo Emerson, whose influence on the construction of America’s mythical individualism can hardly be overstated. In his famous paean to ‘self-reliance’, Emerson casts society in the role of an emasculating and oppressing combatant: ‘Society everywhere is in conspiracy against the manhood[!] of every one of its members. Society is a joint-stock company, in which the members agree, for the better securing of his bread to each shareholder, to surrender the liberty and culture of the eater. The virtue in most request is conformity. Self-reliance is its aversion’. So, to be self-reliant is to reclaim one’s ‘manhood’ and liberty, whereas to be other-reliant in any way is deemed emasculating and restrictive.

Needless to say, this aspect of American identity has remained ubiquitous and it can be seen to motivate the actions of not just Walt, but every adult male character in Breaking Bad. What is more, the pursuit of self-reliance implicitly affirms a doctrine of personal responsibility. This is the idea that you – and you alone – are responsible for yourself. Extending the Lockean basis of private property, the self is literally yours. As a unique and autonomous individual, you possess it and alienate it as you please. Those assenting to this vision of selfhood will likely see Walter White’s ‘self’ as undergoing a linear transformation at the behest of its owner. But in actuality, Walt is increasingly divided between multiple selves. Or, if one insists on the idea of a singular self, then the latter is radically fragmented, disordered and uncertain. Only in the most limited sense can Walt be said to possess his self.

In the ‘Ozymandias’ episode, after Walt has finally been forced to flee his family – that sacrosanct institution so often pressganged into servicing his acrobatic rationalizations – he calls Skyler and knowingly performs an act of confession that is both personal and public (for he is aware of the police’s presence and the implications of this fact). The element of performance here is crucial, for the scene is complicated by Walt’s facial reactions and verbal pauses, which suggest a temporary breaking of character. He doesn’t truly believe what he is saying, but he says it nonetheless to at least put Skyler in the clear. But the cracks in the façade are obvious, for Walt’s hyperbole is straight from the handbook of action-film villainy. Amid his bluster, he exclaims: ‘I built this. Me, alone – nobody else’, reprising Tony Montana’s hot-tub hubris in Scarface: ‘Who put this thing together? Me, that’s who!’ Indeed, this is foreshadowed earlier in the season, in ‘Hazard Pay’, when Walt is shown babe in arms with Holly and Walter Jr. watching the end of Scarface. He and Junior merrily repeat Montana’s climactic outburst (‘Say hello to my little friend!’), much to Skyler’s displeasure. These moments intimate that just as the value of individualism is historically and geographically embedded and reproduced, so the gangsterism of an individual ‘gone bad’ is fashioned after the precedents set by a nation’s culture. The individualist demand to be self-reliant, self-making and non-conformist abjures its own presuppositions, archetypes and exclusions. Moreover, it makes demands of people that cannot be met without access to sets of resources that are not simply unequally distributed, but actively denied certain people.

Following the murder of Hank Schrader, we see Walter White fall to the ground in utter despair, his glasses skewed, his mouth a dark void. The moral boundary of the family has been breached in a most ruthless way. But Walt’s desolation is not just for the immediate event at hand; it is also in recognition of the gulf between his self-image and his reality. Invoking Shelley’s sonnet (from which the episode takes its title), the pomposity of the heroic, empire-building individual – the self-proclaimed ‘King of Kings’, or one might say ‘self-made man’ – is pricked, leaving little beyond ruined lives, prostrated bodies and the hollow words of an egotist in its wake.

As Walt’s delusions of omnipotence reach Randian proportions, they finally produce a grotesque vision of what becomes of the doctrine of ‘personal responsibility’ when it is taken too far. For the same ideology that wants to heap praise on individual victories and successes must also dispense personal blame for losses and failures. Many would likely ‘bite the bullet’ on this point, accepting the inadequacies or yet more ‘collateral damage’. But this belief can lead to some unpalatable situations, as Breaking Bad consistently shows. To take one significant example, consider the disturbing scene in the episode entitled ‘Phoenix’, in which Walt fails to intervene as Jesse’s girlfriend, Jane, passed out after a drugs binge, begins to choke on her own vomit before asphyxiating to death. Walt’s inaction results from a conflict of interests: Jane has blackmailed him, threatening to disclose his activities to the DEA and turn him in, which would mean that his efforts to secure a future for the White family after his death will have been a failure. While we may presume that under normal circumstances Walt would have turned Jane onto her side, the express threat to his family’s inheritance and wellbeing is enough to override any basic compassion. Faced with the relative ‘convenience’ of Jane’s overdose, then, Walt embraces the individualist principle of non-intervention so as to absolve himself of any responsibility.

Of course, this scene is chilling, and Walt’s decision not to act is morally reprehensible. But in a way, what the scene makes painfully present and particular has always been an underlying principle of American individualism. An example pertinent to the original conceit of Breaking Bad is that of the nation’s healthcare, the provision of which follows strictly individualist values. If you fall ill or have an accident and require medical help, it is your prior responsibility to have put sufficient insurances in place to cover the cost of any intervention. The infiltration of the doctrine of individualism into healthcare serves to substantially shift all responsibility from the social to the individual, from the public to the private, confirming a nation built upon a contract of mutual indifference.

To end on a speculative note, perhaps this individualist tradition can also be traced in the use of Walt Whitman to mark a pivotal point in the unfolding of Breaking Bad. While Whitman’s role in the shaping of American identity is canonized alongside Emerson, it might be worth drawing out one of their subtle divergences. For Emerson, the individual self is defined by breaking from the bonds of others, refusing the implied passivity of circumstance and embracing one’s creative powers: ‘But when you have chosen your part, abide by it, and do not weakly try to reconcile yourself with the world. The heroic cannot be the common, nor the common the heroic’. By contrast, Whitman’s individualism is profoundly and unavoidably bound to the universal, the mass, the common voice. It is open, unfinished, fluid, exchanging certainty of self for conditionality, awaiting connection to what is outside itself. The ‘Myself’ of Whitman’s Song is only completed through its environment and other people. Whitman’s ‘I’ is polyvalent and dynamic: ‘I am large. I contain multitudes’. Rather than encouraging isolation, the Whitmanian self extends bridges to other people and things. A deep other-reliance is at work here, which runs counter to the absolute self-reliance of strong individualism established by the likes of Emerson and Thoreau, reproduced in the political field by figures such as Herbert Hoover and later Ronald Reagan, and in the iconic images of frontier masculinity. Since the dramatic narrative of Walter White has so often obeyed the egotism of Emersonian self-reliance, it is only fitting that it is Whitman who receives explicit recognition at the moment of Hank’s epiphanic trip to the restroom.

As the series nears its conclusion, the prominent readings of Breaking Bad will no doubt hold it up as exemplary of a nuanced and detailed psychological account of one man’s dramatic decline from good to evil. But for me, the show stands out for its dual attack: on the social shortcomings (particularly in healthcare provision) that fail so many people, but also on the individualist responses of those who try to ‘go it alone’. The outsourcing of responsibility from the public to the personal is one of the driving forces behind America’s rugged individualism. The most telling moments in the series are those when it pierces the twin veils of psychologism and individualism, and instead illuminates the concentric, web-like structure of relations in which every character is inextricably embedded. Perhaps the appeal of shows like Breaking Bad is so strong because the writers manage to sustain a tonal ambivalence, at once evoking their own cultural history while remaining critical of that history’s blind spots. In the end, Walter White could take a leaf out of Whitman’s book: I am not contained between my hat and boots.

The series finale of Breaking Bad airs Sunday at 9pm on AMC.

The series finale of Breaking Bad airs Sunday at 9pm on AMC.

0 Comments

Be the first to leave a reply!